Germany has been more or less unified for 28 years. The Wall fell in ’89. The Curtain in ’91. Politically, however, things have moved a lot slower. Inside Berlin one of the last battles of the Cold War has only just ended.

This is the story of the German Police “Sommerblouson,” a 70s-era olive green bomber jacket that has become one of the most sought-after vintage items in Europe.

The Sommerblouson checks all the boxes for a cult hit. Iconic design, limited supply, and one hell of an origin story. It is simultaneously woven into the fabric of German culture and banned from civilian ownership in Germany—an enduring remnant of the Cold War and victim to the monolithic power of the European Union.

These days, the Sommerblouson is characterized by its scarcity. Fans search online and off, finding one takes dedication and a whole lot of luck. However, the story of the jacket begins over a half century ago, with searches of a much simpler kind: “Excuse me, zer – are you the police?”

For most of German history, each state was responsible for maintaining (and therefore, outfitting) its own police force. Because of this uniforms varied, and each municipality had its fair share of quirks. Then came 1936.

Under the Nazi government, local departments were merged into a centralized national Ordnungspolizei, a notorious paramilitary organization led by SS officers. The new structure was efficient. The new units were dependable. The Ordnungspolizei would go on to perpetrate massacres throughout occupied Poland.

For obvious reasons, Germany’s first centralized police force soon ceased to exist.

Eager to wipe the slate clean, Allied forces quickly returned policing duties to the German states after the war. Notably—perhaps, admirably—missing from the post-Ordnungs landscape were countrywide police codes. One town’s authorities could dress in blue uniforms; in another, grey. Some even adopted forest green military uniforms. It was decidedly disorderly, a rare exception for a culture defined by meticulousness and order.

The Allies had promised to bring freedom to Europe. In this case, the Americans overshot a little. German Shepherds may be colorblind, but for everyone else, tasks as simple as “get the local policeman” were far from simple. It was obvious that something had to be done, but post-war infrastructure projects proved more necessary.

As Germany entered the height of the Marshall Plan era, all eyes were on rebuilding the Autobahn and the reemergent tourism industry. To borrow an expression: there were bigger wurst to grill.

At the appeal of the German government, Heinz Oestergaard was commissioned to standardize the country’s police uniforms. Fashion designer and couturier to the stars, Oestergaard made a uniform unlike any other. Standard yet different, historic yet modern, it was unlike any of the passé police uniforms seen throughout post-war Europe.

Oestergaard was also a little high on the wave of ‘70s fashion. While other nations clung to conservative pre-war norms, Heinz said “bring on disco.”

Oestergaard’s brave new look for the national police debuted at the height of an era defined by wide-leg trousers, beige shag carpets, and porn star ‘staches. His uniforms were no exception.

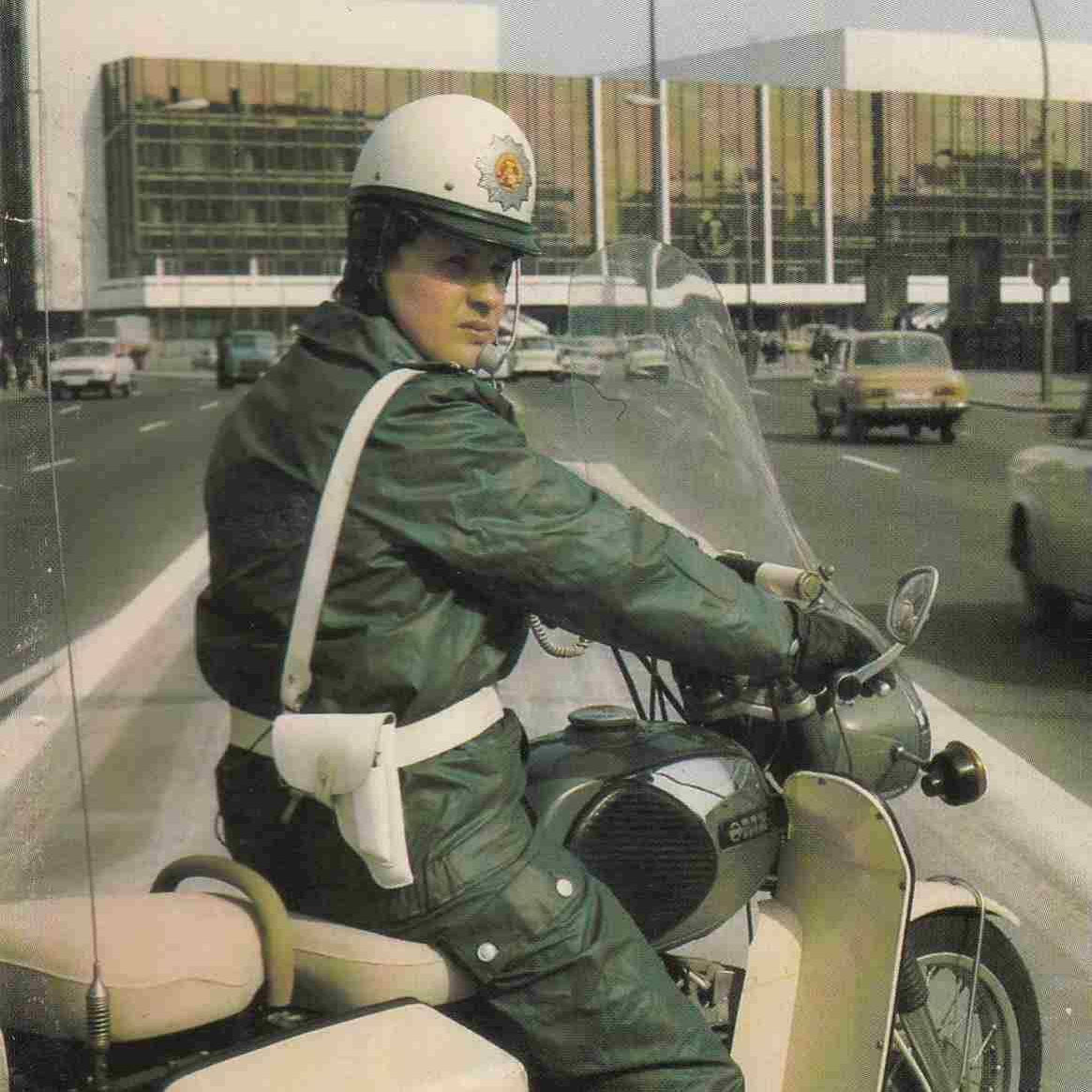

First, there was the color. Unlike most of Europe, Germany’s new police uniforms were neither blue (too French) nor grey (too Russian). Instead, they were “Förstergrün”—a deep forest green better associated with military units than Officer Wiggum.

Then, there were the garments themselves. The basic uniform consisted of three pieces: shirt, pants, and jacket, the latter adorned with a block letter “POLIZEI” on the center-back.

Visible? Yes. Comfortable? Not so much. Officers complained about the stiff, heavy garments and unflattering fits. Notably, the officer’s standard patrol trousers were, according to reports, both poorly cut and “firm as a tent.”

In short, there’s a reason ‘70s fashion is only revived ironically.

Cameras captured the Olympic Village “Munich Massacre” and forest green Polizei dominated the screen. Reporters gave briefings from Berlin, and forest green Polizei sauntered by in the background. Underground punk shows went ‘til the wee hours, and forest green Polizei shut off the lights.

Cartoons of the time even captured the spirit.

Loved or hated, there’s a certain intangible West German-ness about the Förstergrün uniform. It has become a cultural touchstone, something which will exist in the European subconscious for decades to come.

Call it “post-Soviet fashion.” Call it “the ugliest era of menswear.” Whatever you call it, a certain Cold War nostalgia has gripped the world of apparel. Heinz Oestergaard is long dead, but he would be proud knowing his “POLIZEI” gear now commands a spot on Paris runways—with high fashion labels like Vetements riffing on his 50 year old “government work.”

With tensions building towards a second Cold War, Gorbachev’s Europe has found traction in both streetwear and “couture.” In boutiques, Cyrilic-adorned tees by Gosha Rubchinskiy list for close to triple-digits. In Vogue, designer Heron Preston showcases NASA jackets and Russian script sweats side-by-side. Then, there’s the aforementioned Vetements, whose “POLIZEI” sweatshirt resells for – wait for it - close to $1000.

But it’s not just within fashion.

In theaters, Cold War movies are being produced at breakneck speed. Atomic Blonde (2017) and The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (2015) are notable examples in a litany of films to bring the Cold War, and Berlin to the big screen. On the “small screen”, hit shows like Stranger Things and Killing Eve have done the same.

And it’s easy to see the appeal. Say what you will about the Cold War, one thing’s for certain. It was a period defined by unprecedented economic and technological growth, and unrivaled national solidarity and patriotism. As bad as the threat of nuclear annihilation was, the enemy was known and clearly defined in the public consciousness.

In a “post-modern” world defined by intangible threats, indiscriminate violence, open borders, and shifting identities, the Cold War is a comfort blanket for a confused West.

As designers riff on the visual codes of this era, genuine vintage apparel becomes both democratizing (who has $1000 for a sweatshirt?) and differentiating (why look like a poser?). Russian gear—while cool—carries a certain stigma throughout the West because of, well... communism. German gear however, is perceived as sophisticated and aligned with Western values.

It’s in this context that Förstergrün has achieved cultural significance.

Modeled after the American MA-1, the Sommerblouson is a forest green bomber jacket emblazoned with reflective “POLIZEI” lettering across the center back. As a garment, it is simple, well-constructed, and slightly oversized—occupying the same practical “anti-fashion” space that defines Dickies and Carhartt.

As a style piece, it mixes both enduring shapes (bomber jackets) and current trends (military surplus, Cold War nostalgia, the oversized silhouette itself) into something that is as inescapably old as it is – at least, in a world of Vetements raincoats – refreshingly novel.

The lion’s share of that novelty? Simply put, the jacket is scarce.

Once in a blue moon, a Sommerblouson will appear: on a /fa/ thread, on a Grailed listing, or even on actress Sky Ferreira. As soon as it does, a frenzy ensues. Mutli-lingual Googling commences. Imageboards pop off with links alive and dead. Whether decried as a “meme jacket” or sought as the subject of Venmo bribes, one constant about Sommerblouson frenzies will endure: “that stupid fucking jacket” will remain “so god damn hard to find.”

It’s a predictable cycle. Sommerblousons surface; the stock instantly vanishes; and one of the Cold War’s most sought-after vintage pieces inches closer to extinction.

Why the Förstergrün famine? As with most wonky scenarios involving Germany, you can thank the EU.

In 1998, the EU issued a recommendation to all member states, calling on them to standardize all police uniforms to an internationally-recognized dark blue. It made sense on paper: the Schengen free travel area meant more intra-European movement than ever before.

A universal standard would ensure everyone, regardless of nationality or language, would be able to quickly seek help from local authorities. Besides, Brussels argued that many EU members (Britain, France, etc.) already used the dark blue color. The rest were merely—in a convention best reserved for middle managers and high school guidance counselors—“recommended” to switch.

(Swipe to continue reading)

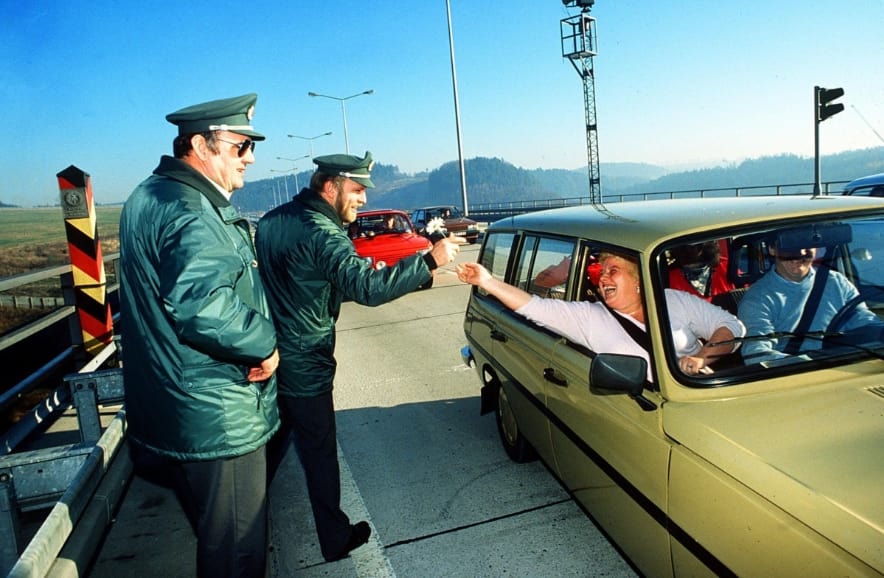

Heeding the EU’s “friendly nudge,” the first German police departments waved auf Wiedersehen to their forest green uniforms in 2004.

Although many German states quickly succumbed to the EU mandate, two states, Bavaria and Saarland, held out. And so, decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a bureaucratic Cold War was declared.

Bavaria, the “Texas of Germany,” slow-rolled the uniform process through internal uniform committees and state-wide votes. As the rest of the country rolled their eyes at “southern stubbornness,” both citizens and government alike took a stand for local identity. After all, the state’s rural police, the Feldgendarmerie, had worn green since their founding post-Napoleon—for Bavarians, it was a matter of heritage.

Saarland, a state famous for its “live and let live” mentality, took an entirely different approach. Unlike Bavaria, Saarland’s police simply didn’t change. While Bavarians puffed out their chests, the Saar performed the political equivalent of a vacation auto-reply. A packed barbecue schedule leaves little time for David-Goliath standoffs; smiling and nodding, however, can be done from anywhere.

This battle of wills—a Cold War over Cold War uniforms - lasted close to a decade.

Then, in 2013, Saarland threw in the towel. Citing the unreasonable cost of new, limited-quantity green uniforms when the rest of the country had gone blue, Germany’s smallest police force officially retired Oestergaard’s designs. Two years later, Bavaria polled all 27,000 members of its police force. After a majority decision, it too, announced it was switching colors.

The Conflict Was Over.

46 years after their introduction, the last Förstergrün uniforms were retired from service. In the ensuing months, Bavaria and Saarland would unceremoniously begin the process of liquidation, handing over their stock to the German public auction authority and ordering blue.

Reviving The Bomber

The Heart of KommandoStore

KommandoStore launched in 2013 out of a basement in St Paul, Minnesota. At heart, we’re a military surplus store. Nine years on, we’ve had opportunities to do a little more than that.

Does the gear look cool? Hell yeah. A decade plus is is a lot of time to figure out what’s worth importing, and we don’t waste time with the dumb stuff.

What really matters though, are the stories behind the gear—of circumstance, of courage, of genius, and of sacrifice. A designer made the Sommerblouson; history gives it context and meaning.

Taking it Up a Notch

Year after year we are upping our commitment to revivals and making our own stuff in general. This means well researched long form content focusing directly on what we’re most passionate about.

It means working with the original manufacturers of iconic military items, preserving things that would otherwise fade into obscurity.

In The End

It started with the Sommerblouson, manufactured in Germany by the same company who supplied Bavaria and Saarland until the bitter end. Where the revivals end, well that’s up to you...